Make illegal states unrepresentable¶

The mantra “make illegal states unrepresentable”, popularised by Yaron Minsky’s lecture on Effective ML, is a commonly-used guideline to help design robust ways of “modelling” data. While it is often hard to do this perfectly, it is a very helpful technique to keep in mind.

There are many blog posts and articles about this principle, using many different programming languages. Some of these have examples that aren’t very compelling, some are almost anti-examples in my opinion, and many will be confusing if you don’t know other languages. So here is my take on it, using best practice modern Python.

Before reading:

See Context and assumptions .

It is assumed you have basic understanding of type hints. Some good resources are:

Python Type Checking Guide on RealPython, especially the first few sections

The mypy Type hints cheat sheet

The example¶

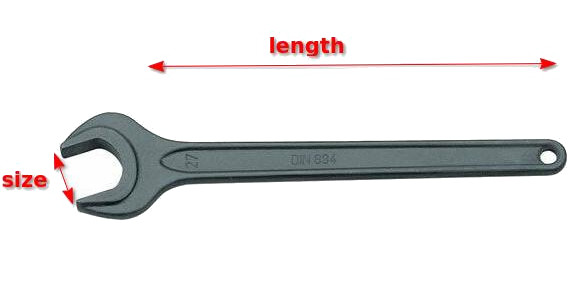

We have a system that wants to store information about physical tools, including hammers and spanners and so on. Maybe these tools will be used in a factory, maybe the program is part of code for a physical robot, maybe it’s for a game where these tools play a role.

Let’s start with a class that stores some basic information about a spanner. We’re going to use modern Python idioms, which means that we define these simple classes using dataclasses, rather than writing a custom __init__ method. So it will look like this:

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass(frozen=True, kw_only=True)

class Spanner:

size: float

length: float

mass: float

(At this point, I’m not going to worry about units, or exactly what the measurements are, or whether the spanner-nerds are going to object to this. Let’s say the units are in mm and grams, and leave it at that…)

We can now make any spanner we want:

my_spanner = Spanner(size=10, length=150, mass=500)

We may have a whole load of code that deals with spanners – boxes that can store spanners, maybe code that shows a visualisation of each spanner etc.

Now, suppose somewhere in this system we want to know whether a specific spanner could be used with a specific nut. We’ve got some simple nut class:

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass(frozen=True, kw_only=True)

class Nut:

size: float

And we’ve got a very simple function that takes a nut and a spanner and checks they are compatible:

import math

from .nuts import Nut

from .spanner1 import Spanner

def does_spanner_fit_nut(spanner: Spanner, nut: Nut) -> bool:

return math.isclose(spanner.size, nut.size)

(Here we’re using math.isclose() as is best practice when using float, rather than simple equality)

The change¶

All is fine so far. But then, we realise that we have another type of spanner – adjustable spanners.

We now need to make some choices about how to adjust our code. For these spanners, the size field doesn’t really make sense any more – we instead want something like max_size. We avoid the temptation of having a single size field and giving it two different meanings – that would be asking for trouble.

First attempt¶

We decide that we’d like to be able to write this:

normal_spanner = Spanner(size=10, length=150, mass=500)

adjustable_spanner = Spanner(max_size=20, length=150, mass=500)

So we end up with a class definition where we add the max_size attribute, but make it optional. We also need to adjust the size and make that optional too, otherwise our tools will complain. Making it optional here means:

We add a default value of

Noneto the field.We change the type annotation to allow

None

So it looks like this:

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass(frozen=True, kw_only=True)

class Spanner:

length: float

mass: float

size: float | None = None

max_size: float | None = None

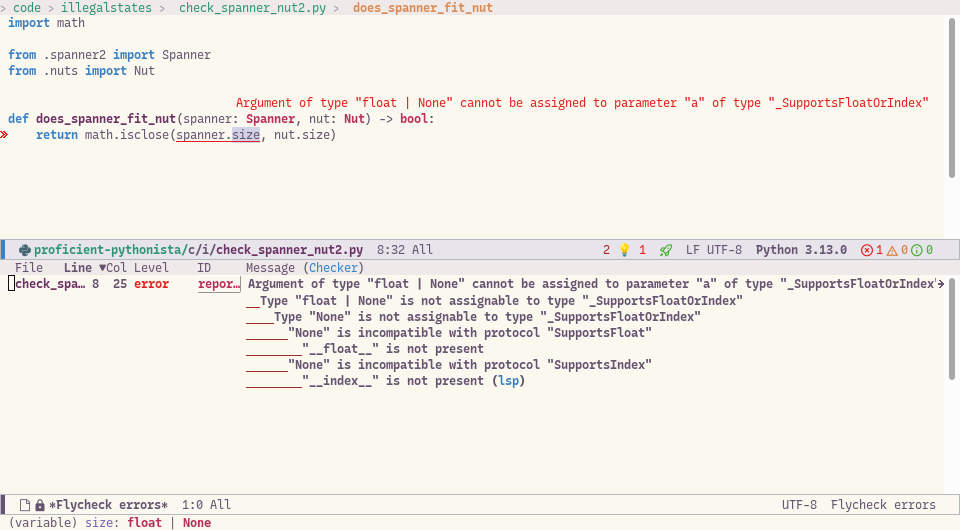

Our first problem is that we now have to adjust our does_spanner_fit_nut function. The good news is that the type checker has immediately flagged an error:

Pyright complains:

Argument of type “float | None” cannot be assigned to parameter “a” of type “_SupportsFloatOrIndex” in function “isclose”.

This error is perhaps a little obscure, but we get the idea – spanner.size could be None, instead of float, in which case we

can’t use math.isclose().

So now we need to update this code, adding in a branch that supports the max_size attribute, and using some isinstance() checks to exclude the possibility of attributes being None. It could look like this:

import math

from .nuts import Nut

from .spanner2 import Spanner

def does_spanner_fit_nut(spanner: Spanner, nut: Nut) -> bool:

if isinstance(spanner.size, float):

return math.isclose(spanner.size, nut.size)

if isinstance(spanner.max_size, float):

return spanner.max_size >= nut.size

However, your editor/static type checker will now rightly complain:

Function with declared return type “bool” must return value on all code paths

Our code has a problem – what if someone creates a Spanner with both size and max_size set to None? We’ve done nothing to prevent that, and the static type checker is rightly pointing out that in this case, it is possible to get all the way through does_spanner_fit_nut() and “fall off the bottom”, in which case the function will return None. This isn’t what we want at all – it’s a bug.

Quick fix 1¶

Our first approach is what we might call the “validation” approach. We can add some code to the end of does_spanner_fit_nut() that raises an exception:

import math

from .nuts import Nut

from .spanner2 import Spanner

def does_spanner_fit_nut(spanner: Spanner, nut: Nut) -> bool:

if isinstance(spanner.size, float):

return math.isclose(spanner.size, nut.size)

if isinstance(spanner.max_size, float):

return spanner.max_size >= nut.size

raise AssertionError("Spanner must have at least one of `size` or `max_size` defined")

Now our static type checker is happy — it can see that the function will either always return True or False, or raise an exception, which is a different type of thing. The error won’t silently pass, and our function that is annotated as returning bool won’t ever return None instead.

The big problem with this fix is that the validation is happening far too late:

It’s happening at runtime – you’ll only see you have a problem when you actually run the code. We’d like to eliminate this kind of error before then, and be sure that it can’t possibly happen.

If this exception is raised, we’ll get a stack trace showing a problem with a spanner at the point we try to use the spanner and call

does_spanner_fit_nut(). The bug in the code, however, happened elsewhere, at the point we created this impossible spanner. We should never have created a spanner with bothsizeandmax_sizeset toNone. When we see the exception, all we know is that somewhere in the code base we’ve created a badSpanner, and we now have to search for every place that creates aSpannerobject and check.

Quick fix 2¶

Our second attempt to fix this involves moving the validation closer to the problem. Specifically, we can put the validation inside the initialiser of Spanner (sometimes imprecisely called the constructor). That method is usually __init__. In our case, we are using dataclasses, so the __init__ method is written for you. But dataclasses do provide a little hook for your own logic, called __post_init__, where we can put our validation. It looks like this:

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass(frozen=True, kw_only=True)

class Spanner:

length: float

mass: float

size: float | None = None

max_size: float | None = None

def __post_init__(self) -> None:

if self.size is None and self.max_size is None:

raise AssertionError("Spanner must have at least one of `size` or `max_size` defined")

It’s now impossible to create an illegal spanner, and we’ll get an exception at the point in the code that attempts to do so:

>>> Spanner(length=1, mass=2)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<python-input-1>", line 1, in <module>

Spanner(length=1, mass=2)

~~~~~~~^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

File "<string>", line 7, in __init__

File "/home/luke/devel/proficient-pythonista/code/illegalstates/spanner3.py", line 13, in __post_init__

raise AssertionError("Spanner must have at least one of `size` or `max_size` defined")

AssertionError: Spanner must have at least one of `size` or `max_size` defined

This is a big improvement. We now know that there won’t be impossible spanners going through the system, and for buggy code that tries to make them, the stack trace shows the actual bad line of code.

There are still significant problems though.

First, there are actually more illegal states that we haven’t yet addressed. What about a Spanner with both size and max_size set to floats? What does that mean, and what should does_spanner_fit_nut() do with that?

More critically, our change hasn’t made does_spanner_fit_nut() any easier to write. We now know that the final raise AssertionError won’t ever happen, which is in some ways good. But:

We only know that because we know about some other code that runs. We can’t use just local reasoning to be certain of it – we need to know the other code, and we need to be sure the other code hasn’t changed since we last looked at it.

The type checker doesn’t know about the logic we put in the

__post_init__method, and so if we try to remove theraise AssertionErrorvalidation fromdoes_spanner_fit_nut(), it will complain at us again. Type checkers rely on types as their source of truth, and can’t do advanced logic based on code that checks values, especially if that code is in a different part of the code base.This also means we’ve now got duplication – the same validation is running in multiple places, which means it could easily get out of sync.

Can we do better?

The better fix¶

The answer is to move our check to the type level, changing the definition of our type to make it impossible to even represent the illegal state.

What we want to express is this. A valid spanner is either:

A normal spanner with a valid

sizeAn adjustable spanner with a valid

max_size

But not:

a spanner with neither or both of these attributes.

We can achieve this by having separate types for the two cases. We need some new names, so our normal spanner will be called SingleEndedSpanner (anticipating that we might have DoubleEndedSpanner soon), and we’ll also have AdjustableSpanner. Depending on the existing code,

we might want to use renaming functionality in the editor to achieve this. Alternatively, we might deliberately break everything and give it a different name manually, so that we can use type checking tools to find the code that might need updating.

In this case, several of the attributes of spanners, like length and mass, are common to both kinds of spanner. To avoid duplicating code, we’ll pull these out as a base class which we can then inherit from.

Finally we’ll make Spanner into an alias that means “SingleEndedSpanner or AjustableSpanner”. This is a union type, also called a “sum type” in some communities.

The code looks like this:

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass(frozen=True, kw_only=True)

class SpannerCommon:

length: float

mass: float

@dataclass(frozen=True, kw_only=True)

class SingleEndedSpanner(SpannerCommon):

size: float

@dataclass(frozen=True, kw_only=True)

class AdjustableSpanner(SpannerCommon):

max_size: float

type Spanner = SingleEndedSpanner | AdjustableSpanner

It’s important to note that our new Spanner type exists really only for the benefit of static type checking and writing type signatures more succinctly. Spanner isn’t a “concrete” type like SingleEndedSpanner or AdjustableSpanner and there are no objects for which type(obj) == Spanner.

This technique doesn’t always require new classes. Sometimes it can be just a different arrangement of existing types, often using type unions, or lightweight types like tuples.

Having done this, what does does_spanner_fit_nut() look like? It can be reduced to just this:

import math

from .nuts import Nut

from .spanner4 import AdjustableSpanner, SingleEndedSpanner, Spanner

def does_spanner_fit_nut(spanner: Spanner, nut: Nut) -> bool:

if isinstance(spanner, SingleEndedSpanner):

return math.isclose(spanner.size, nut.size)

if isinstance(spanner, AdjustableSpanner):

return spanner.max_size >= nut.size

In this case, our type checker will correctly not complain at us — it understands the Spanner type alias, and can see that all cases are covered.

In some cases, if you are writing code like this, it can be important to ensure that you are getting exhaustiveness checking using an explicit assert_never. So it’s a good practice to add it in, like this:

import math

from typing import assert_never

from .nuts import Nut

from .spanner4 import AdjustableSpanner, SingleEndedSpanner, Spanner

def does_spanner_fit_nut(spanner: Spanner, nut: Nut) -> bool:

if isinstance(spanner, SingleEndedSpanner):

return math.isclose(spanner.size, nut.size)

if isinstance(spanner, AdjustableSpanner):

return spanner.max_size >= nut.size

assert_never(spanner)

You may notice that your editor greys out the last line and gives a message like this:

Type analysis indicates code is unreachable

This is a reassuring sign you are doing it right – on the assumption that this function is being passed a Spanner object (which should also be checked by the type checker), there is no way that we can get to the last line, and the type checker is now explicitly confirming that to us. If something changed, like we added DoubleEndedSpanner as another option in the Spanner alias, this line would immediately become a type error, and our code wouldn’t pass static type checks, which is what we want.

With modern Python and the match statement, there is also a nicer way to write this code. The isinstance checks turn into “pattern matching” that pulls out the field values:

import math

from typing import assert_never

from .nuts import Nut

from .spanner4 import AdjustableSpanner, SingleEndedSpanner, Spanner

def does_spanner_fit_nut(spanner: Spanner, nut: Nut) -> bool:

match spanner:

case SingleEndedSpanner(size=size):

return math.isclose(size, nut.size)

case AdjustableSpanner(max_size=max_size):

return max_size >= nut.size

case _:

assert_never(spanner)

Parse don’t validate¶

The approach above is sometimes called parse don’t validate. We’ve already seen the “validation” approaches, and how they had limited effectiveness. To understand the “parse” bit, imagine that we were pulling in some data about spanners from a CSV file.

Maybe the data is in some format like this, where, contrary to our wisdom, they decided to combine the size and max_size fields into a single column:

Type |

Size |

Mass |

Length |

Adjustable |

30 |

300 |

150 |

Single ended |

12 |

500 |

180 |

When parsing the data, we might want to reject any invalid rows. The “validate” approach might look like this:

parse the data into

dictobjectscollect error messages for anything which isn’t valid

return the

dictobjects and errors

The problem is that dict objects are very unstructured – they are just bags of data that could be anything. Later code will still need to deal with those dicts, which could have any number of problems. The validation function has made some guarantees, but hasn’t “captured” those guarantees in any way that helps the rest of our code.

If the code that parses the CSV files instead were to return our initial Spanner object, it would improve things a bit, but we really want it to go all the way and parse into the most tightly defined objects we can – our SingleEndedSpanner and AdjustableSpanner objects.

Product and sum types¶

In the programming world, you will often come across the terms “sum types”, “product types” (and “algebraic data types” which is a fancy way to refer to sum and product types). It’s helpful to understand these concepts and use them to think about this problem.

The simplest example of a product type is a tuple. Consider a 3-tuple which contains 3 booleans. In Python the type hint might look like this:

x: tuple[bool, bool, bool]

Valid values look like this:

x = (False, False, False)

x = (False, False, True)

x = (False, True, False)

...

How many possible values can x have? A little reflection yields the value 8 — there are 2 valid values for each position, and you can have any combination, so it’s 2x2x2. The number of possible states is the product of the number of states at each position.

Tuples are not very descriptive, so often we want to use names for each field, which we can do with a simple dataclass. The above tuple might represent options for something e.g.:

@dataclass

class MyGuiOptions:

show_sidebar: bool

show_menubar: bool

enable_keyboard_shortcuts: bool

This is just the same as the tuple in terms of number of states, we’ve simply added names for each field. Classes like this are also product types.

Let’s now consider the case of union types. Suppose we want to represent the sign of a number, and we want to represent it with an integer: -1 for negatives, 0 for zero, +1 for positives. We can represent this in Python using something like this:

type SignOfNumber = typing.Literal[-1, 0, 1]

Now consider the following union type:

type MyWeirdThing = SignOfNumber | bool

How many different values could an object of type MyWeirdThing have?

In this case we can list them quite easily:

-101FalseTrue

Clearly, the total number of possible values is equal to the sum of the number of possible values for each of SignOfNumber and bool, because the object could be either a SignOfNumber or a bool. This is why “sum type” is just another name for “union type”.

Thinking back to our original example, our first Spanner class was a product type – a dataclass with a number of fields:

@dataclass

class Spanner:

size: float

length: float

mass: float

We then considered switching out size for two optional fields:

@dataclass

class Spanner:

size: float | None

max_size: float | None

length: float

mass: float

Now, each of size and max_size has become a “sum” or “union” type, which means it gains another possible value: it can be None as well as any float value. But because these are part of the larger product type, the possible combinations multiply together. And those combinations include unwanted ones like Spanner(size=None, max_size=None).

It can be helpful to imagine the above code with * and + signs:

class Spanner:

size: (float + None)

*

max_size: (float + None)

*

length: float

*

mass: float

When you “multiply out” the brackets, thinking about just the first two fields, you get this, where we can clearly see the illegal states:

(size: float * max_size: float) +

(size: None * max_size: float) +

(size: float * max_size: None) +

(size: None * max_size, None)

Instead of this, our preferred solution instead looks like the following:

@dataclass

class SingleEndedSpanner:

size: float

@dataclass

class AdjustableSpanner:

max_size: float

type Spanner = SingleEndedSpanner | AdjustableSpanner

We’ve still added a union, but just one, and at the right place. The number of additional possible states has been minimised, and most importantly we haven’t added new illegal states.

Limitations¶

While we have the ideal of avoiding all illegal states, often practical considerations come in. For example, all the above Spanner types have the issue that they could have a negative size or length or mass field, which obviously makes no sense. Avoiding this problem by introducing a new PositiveNumber type would be possible, but might be a pain in the neck for various reasons. It might also not really gain you much in terms of preventing the kind of bugs that are likely to happen, or making it easier to write code.

There are many other cases where there are trade-offs, and a pragmatic approach should be taken. Often, you will get significant benefit from putting validation inside the __init__ or __post_init__ method.

Summary¶

The key aims in the principle “make illegal states unrepresentable” are these:

Make it impossible for your system to have objects that would represent illegal states or values.

Capture the constraints you want to impose at the level of types, so the type checker can make use of that information.

Design code so that both the human reading the code and the static type checker are able to use local reasoning to see whether code is correct and complete.

The methods used to achieve this are:

Identify invalid states by thinking about where you have product types instead of sum types, and are multiplying possible states instead of adding them.

Split types/classes into more but “smaller” types/classes that represent just the valid states. Sometimes this might mean pulling out a few related fields as a group.